Timeline project documents Harvard’s long history of Islamic studies

Harry Bastermajian (left) and Meryum Kazmi have compiled an archive project documenting the history of Islamic studies at Harvard. Their archival discoveries show a connection with the Islamic world going back as far as the University’s founding. Below: Kazmi and Bastermajian examine notes from Hamilton Gibb, who taught at Harvard in the 1950s.

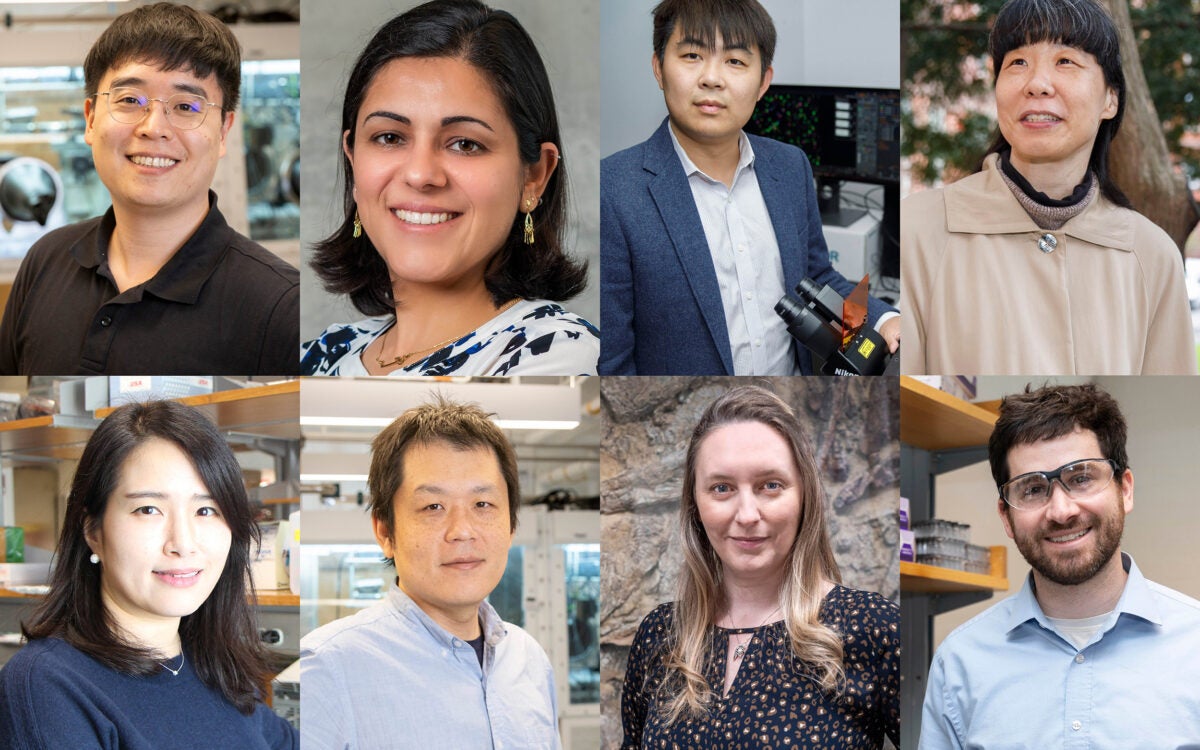

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

When Harry Bastermajian inherited a collection of notes from Sir Hamilton Gibb in 2016, he said it was like viewing a time capsule. He had recently become executive director of the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program at the time, and the notes from the prominent Islamic studies professor who taught at Harvard in the 1950s and ’60s offered a valuable glimpse into historic debates on the best way to teach Islamic studies.

“It gives a good window into how people thought about the study of the world, and how they wanted to organize what we now call ‘global studies’ or ‘international studies,’” Bastermajian said.

Bastermajian and Meryum Kazmi, the program’s senior coordinator of programming and engagement, recently completed an archival project on the history of Islamic studies at Harvard, featuring an interactive timeline that illuminates the eras of scholarship from the earliest days to the present.

The first era was the University’s 17th century clergy training days, when the study of Arabic was mainly for understanding Biblical Hebrew, according to Bastermajian. Harvard’s first presidents, Henry Dunster and Charles Chauncy, were “Orientalists” (scholars of Eastern language and cultures). Arabic instruction began during Chauncy’s presidency and was likely taught by Chauncy himself.

“When I think about colonial New England, the study of Arabic is not something I would have realized existed here,” Kazmi said. “The fact that early Harvard presidents studied and were interested in Arabic and encouraged its study shows Harvard’s connection with the Islamic world is really as old as the University itself.”

The second era, in the late 19th century, focused on Muslim interactions with Europe. The 1836 arrival of Professor Crawford H. Toy brought a “turning point,” and Harvard’s first Islamic studies course: history of the Spanish Califate. Toy’s courses explored Islamic history in India, Egypt, Sicily and the Barbary States, and the Crusades via Muslim sources.

“It was introduced to the History Department to get students to think more globally, which is something we still encourage our students to do,” Bastermajian said.

The third era, post-World War II, was about understanding the Middle East to further U.S. interests abroad. Professors like Gibb aimed, during this time, to move studies beyond “Orientalism” and the European focus, in favor of an interdisciplinary approach. The final era saw robust development of Islamic studies on campus, with the addition of programs like the Islamic Legal Studies Program, the Middle East Initiative and the Alwaleed program.

Bastermajian said the archive project reinforces the importance of studying the impact of Harvard scholars like Toy, Gibb and others, in order to understand the resulting scholarship.

“Doing this kind of research, you get to see the connections that exist between how we approach the study of history, the study of cultures, the study of religion,” Bastermajian said, “how it’s changed over time, but how there are linkages with how we approached it in the past.”

The timeline and corresponding podcast episode, featuring former program directors, can be found on the program’s website.